As The Office‘s Michael Scott (unintentionally) points out: in this day and age, we so fervently avoid stereotypes, circumventing issues of race, gender, sexuality, etc. altogether, that we often end up sounding more ridiculous and offensive. While it is certainly important and ideal to treat everyone equally regardless of their racial identity, in reality this does not always pan out, namely within the art world. How does the racial identity of an artist affect how they produce artwork, and how it is viewed by the masses? How does the historical presence of racial discrimination within art affect contemporary multi-cultural artists and their work? Is talking about an artist’s gender, racial or sexual identity in relation to their work celebratory or divisive?

As discussed in a previous post, Art History as a discipline faces an uphill battle when trying to highlight and define “good art” to the masses; without fail, we end up neglecting plenty of good artists who, for one reason or another, didn’t make the “top 100” list. As humans, we tend to have a need to categorize in order to understand; Because of this, we end up unintentionally marginalizing some groups and glorifying others, depending on the identity of the storyteller recounting history. Because mainstream history has been written by the elite and, at the very least, the literate, what happens to the marginalized cultures who rise up after being unable to present their side or the story for so long? When they finally gain the ability to speak for themselves, how do they choose to do so?

These questions unravel further questions when dealing with African-American artists, and in defining the ever-evolving identity of African-Americans within art: How do we define African-American identity in art? How do we reconcile African-American art within the larger context of Art History? Most importantly, are we paying attention to how each artist defines his or herself, as opposed to how we define them?

Artist Kerry James Marshall discusses the desire among black artists to be referred to simply as “artists,” without the need to insert a qualifying racial identifier in their title.

Cultural identity is defined just as much by its own members’ search for and creation of definition as it is by the perceptions and propaganda of others and, more specifically, by those in power.

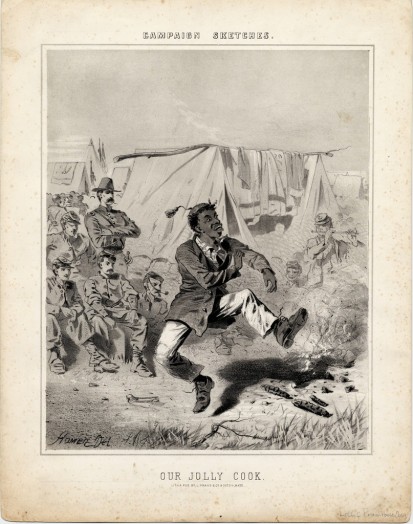

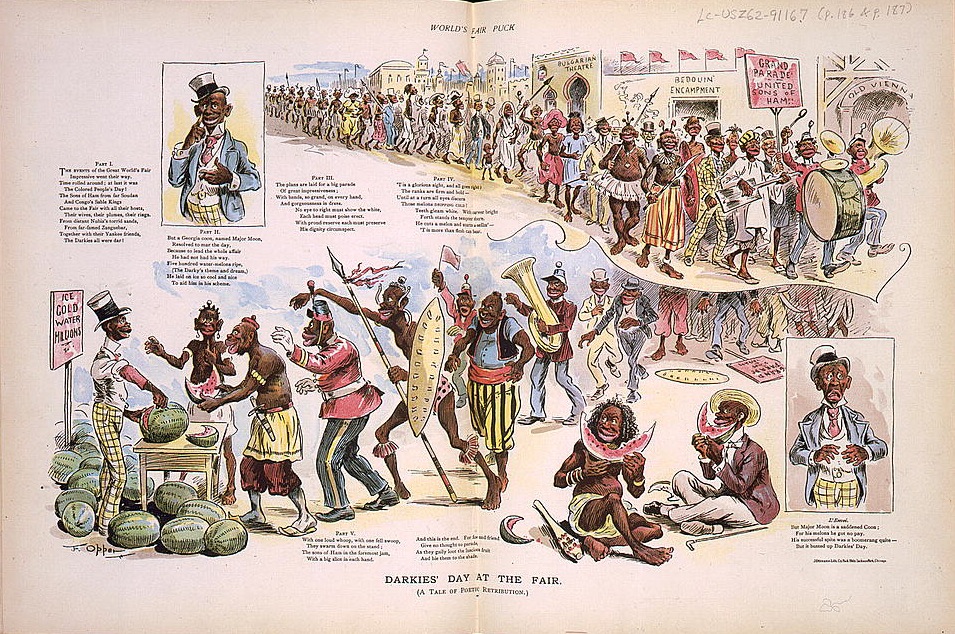

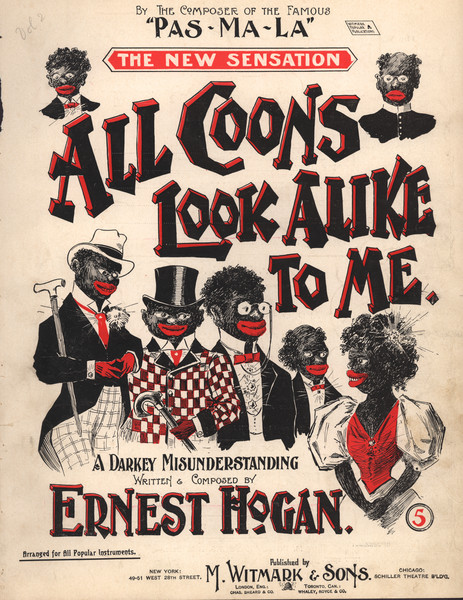

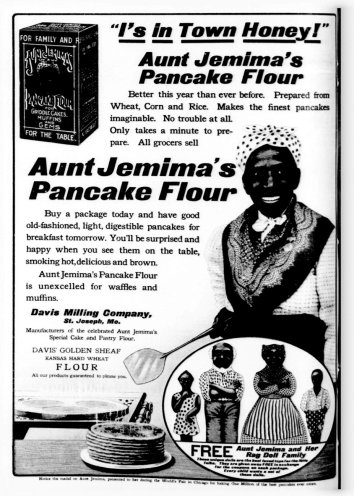

Both before and after the Civil War, African-Americans were depicted by mainstream visual culture as caricatures, both as an attempt by the white mainstream to define what it didn’t understand, and to keep from elevating the status of African-American culture. This took an obvious form in the “mammy” archetype, as well as artwork relegating African-Americans to subservient roles, such as entertainer, cook, caretaker and servant.

Images from the mid to late 19th century stereotyped and caricatured physical features of African-Americans, as well as items that still connected black culture to slavery (such as watermelon, which was easy and cheap to grow on plantations, and given to slaves to avoid dehydration while working long hours in the fields).

Our Jolly Cook (from Campaign Sketches), Winslow Homer, 1863, Lithograph, Virginia Historical Society, bequest of Paul Mellon

Darkies Day at the World Fair, Frederick Burr Opper, c. 1893, lithograph, color. Composite of caricatures of black people, many of them in various costumes, at Chicago World’s Fair.

The “mammy” archetype was characterized as a maternal, de-sexualized, non-threatening female domestic role, often depicted as grossly overweight, hostile toward men, and usually a form of “sassy” comic relief.

This Mammy stereotype was perpetuated, and still is, through popular advertising.

So, if you are an African-American artist living amongst this degree of cultural stereotype, how do you reconcile this in your own work? Do you acknowledge your heritage and racial identity in your art? Or do you choose not to highlight what makes you “different” in order to be recognized as a member of the established mainstream? Is there a middle ground?

During the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural movement in the 1920s and 1930s characterized by an explosion in African-American literature, music and art, there existed a heavy focus on re-conceptualizing African-American identity. Writer and philosopher Alain Locke (1855-1954) encouraged artists of the early 20th century to celebrate their race by representing African-American subjects, and looking to African traditions in order to illustrate a sense of cultural pride and interest.

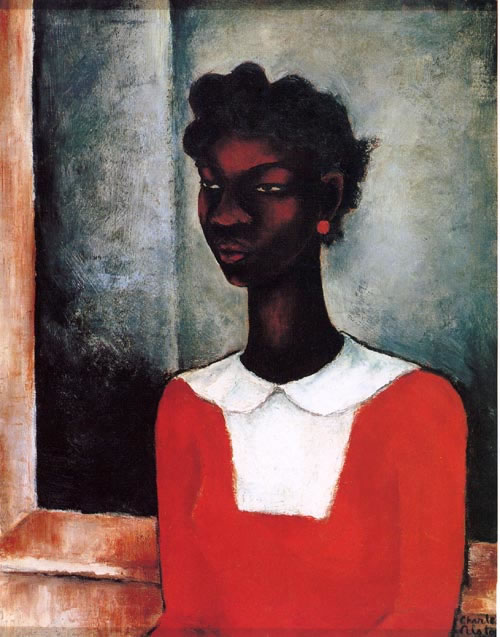

Charles Alston’s portrait Girl in a Red Dress (1934) depicts an African-American woman without trace of caricature or stereotype; he represents her as a a portrait sitter in the European painting tradition, in modern, fashionable dress with a somber but intent facial expression. The portrait contains a sense of psychological depth that you do not see in the cartoons or stereotyped images above; Alston shows her as beautiful and cultured, while still drawing on elements seen in traditional African art (ie: tribal masks) within her facial structure. Portraiture, a “safe” subject matter for emerging artists in the late 19th century and early 20th century, involved patrons, and therefore was a stable way to make a decent living as an artist. Other scenes depicted by African-Americans involved dramatic renderings of the hardships of slavery, or turning to African art motifs as an attempt to discover and establish African-American identity in the arts.

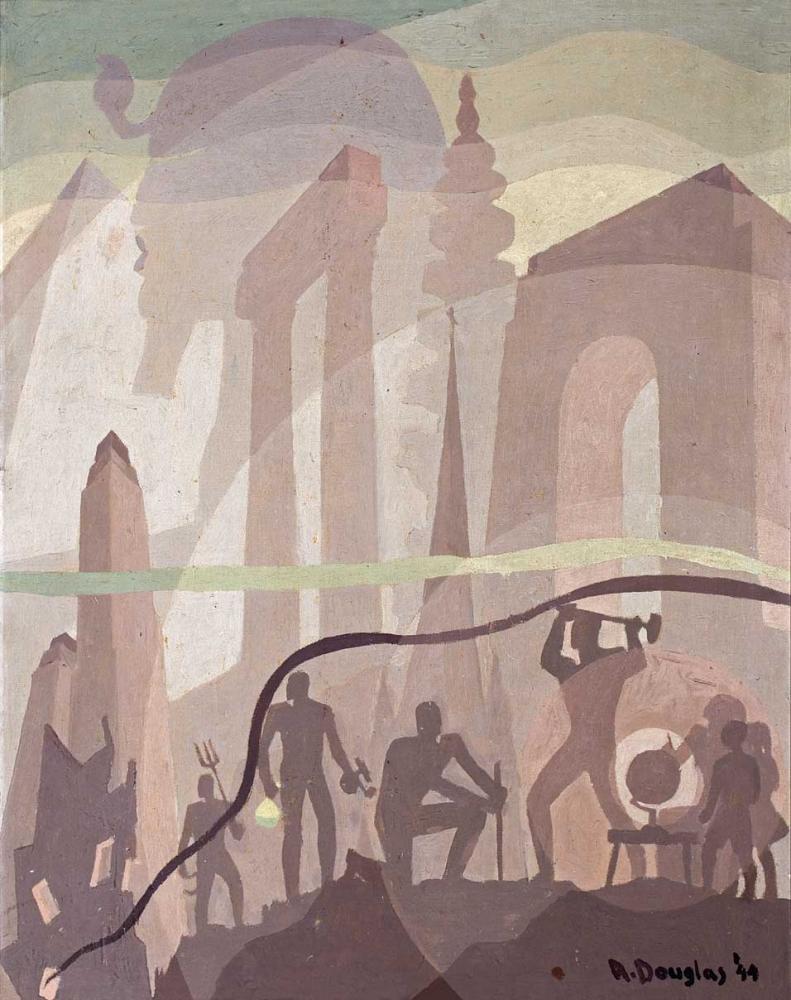

For example, Aaron Douglas chose to make more direct references to African history in his work, as seen in his Building More Stately Mansions (1944). Douglas uses a restricted palette, geometric designs and silhouetted figures to give his composition a sense of Primitivism and reference artistic styles seen in Egyptian art. In his painting, he reclaims Egypt as a piece of African past, and uses it to symbolize nobility and progress of his people.

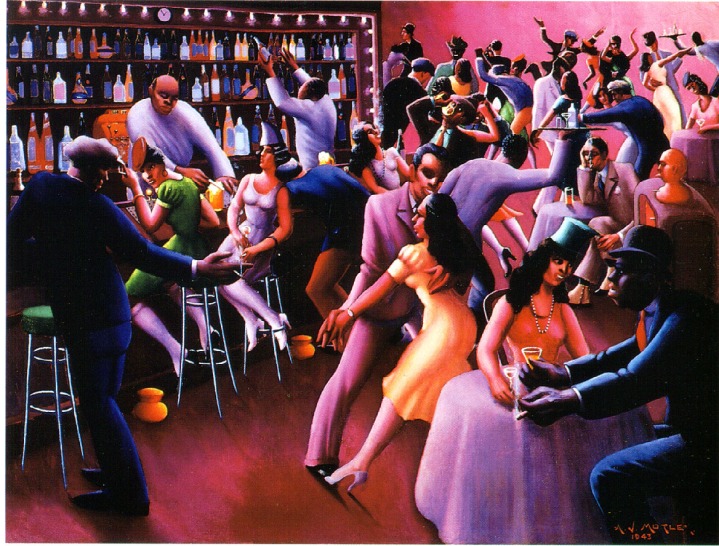

Archibald J. Motley, Jr., was a Chicago artist and graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (where many of his paintings now hang). Motley’s wanted to honestly represent African-American culture beyond adhering to any racial restrictions or stereotypes. He painted black urban life as he saw and experienced it, illustrating genre scenes (events from daily life), in an attempt to bridge the race gap. In Motley’s own words: “I’ve always wanted to paint my people just the way they were.”

For added effect while you look at Nightlife, listen to Charlie Parker & Dizzy Gillespie recording below.

Like art and literature during the Harlem Renaissance, music was flourishing, especially in African-American communities near big cities. The jazz movement, namely Bebop jazz, particularly reflects Motley’s style (fast-paced and lively tempo, disorganized and improv-esque use of instruments). Imagine happening upon Motley’s scene in a smoky, dimly lit room at 1:00am with bottles clanking, people laughing and even a few drunks falling asleep at their tables with lit cigarettes hanging from their mouths. As you look at this piece, your eyes literally move around Motley’s composition to a beat, tracing the diagonals of the arms and legs from the bottom of the painting, through the crowd and to the top. The lines within the painting create rhythm, while the overall red tone sets the mood. Many of the chraracter’s facial features reference traditional African art while still giving each person an individual personality and role within the composition. Motley does not directly discuss stereotypes, nor historical events; he simply aims to show a group of young urbanites in their regular, nightly environment.

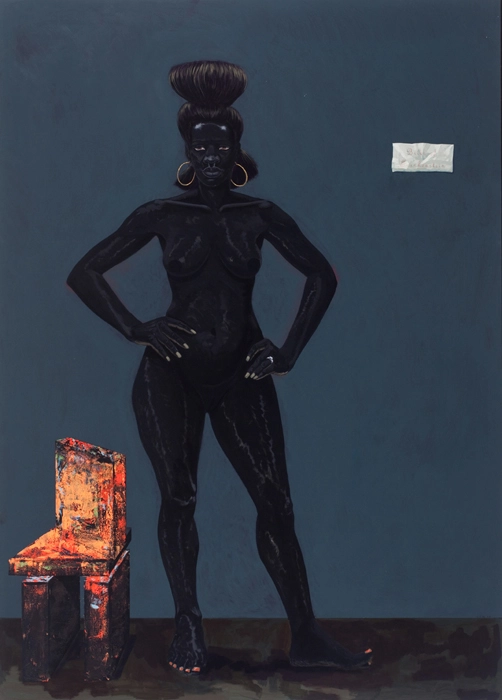

This racial and cultural dialogue has not ended. Contemporary artists still discuss and confront issues of race and art. Kerry James Marshall, who was seen in the video toward the beginning of this post, confronts marginalized black history by re-appropriating historical African images to become more heroic within in his own work, and by emphasizing skin color.

Untitled by Kerry James Marshall, 2009 acrylic on pvc 61 1/8 x 72 7/8 x 3 7/8 inches

Another contemporary artist, Kara Walker, mainly utilizes figural and narrative silhouette paper cut outs to comment on race relations in past and present America. All of her figural cut outs, regardless of race, are rendered only in black paper, therefore not allowing the viewer to differentiate between ethnicity based on skin tone. Instead, these racial variations can only be identified through stereotypical facial features that Walker emphasizes on purpose (ie: obscenely large lips on African-American figures). This is meant to make you uncomfortable and question your own stereotypical notions about different races. Her silhouettes are detailed further in a previous post.

Detail of Gone, An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart, 1994

W.E.B. Dubois, an author, historian and co-founder of the NAACP, describes a notion of double-consciousness in the lives and minds of African-Americans–an identity split into factions, both insider and outsider–and having to reconcile one’s identity as seen within one’s own culture, with how one is seen and critiqued by the mainstream culture:

It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

Some artists choose to confront race as directly as possible in their work, even making the audience question their own identities. Adrian Piper’s famous 1988 video installation piece entitled Cornered shows Piper, a light-skinned African-American, speaking to her audience directly about her blackness, and how her acknowledgment of her race may make the audience feel. Not only that, but she discusses the notion that a majority of white people statistically have black ancestry, and how being presented with that information makes the audience feel. She implicates everyone, black and white, as part of the problem and part of the solution.

I’m black. Now, let’s deal with this social fact and the fact of my stating it together. Maybe you don’t see why we have to deal with it together. Maybe you think this is just my problem, and that I should deal with it by myself. But it’s not just my problem, it’s our problem….You see, I have no choice. I’m cornered. If I tell you who I am, you become nervous and uncomfortable or antagonized. But if I don’t tell you who I am, then I have to pass for white. And why should I have to do that? …..You may be reacting to what I’m saying as just an empty academic exercise that has nothing to do with you. But let’s at least be clear about one thing: this is not an empty academic exercise. This is real. And it has everything to do with you. It is a genetic and social fact that according to the entrenched conventions of racial classification in this country, you are probably black. So if I choose to identify myself as black whereas you do not, that is not just a special personal fact about me. It’s a fact about us. It’s our problem to solve, so how do you propose we solve it? What are you going to do?

While this post is meant to give an overview of ideas related to racial identity within art, obviously these ideas only represent a select few points of view within a broad and beautiful artistic culture. As much as I’d like to, I cannot possibly cover everything within the history of African-American Art (ie: I would love to write another post solely dedicated to African-American art of the 1960s and 1970s, and another to discussing Jean-Michel Basquiat’s life and work). Every artist mentioned here, and so many more, deserve their own museum catalog, let alone blog post.

Sources: **Note: A large portion of the references and ideas presented in this post came from a course called “The Black Aesthetic,” created and taught by Professor Jordana Moore Saggese at Santa Clara University in the Winter of 2008. Saggese currently teaches at California College of the Arts in San Francisco.

Locke, Alain. “The Legacy of the Ancestral Arts,” from The New Negro (1925). Published in Hills, Patricia, editor Modern Art in the U.S.A.. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2001, 73-76.

Amy M. Mooney, “Representing Race: Disjunctures in the Work of Archibald J. Motley, Jr.” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, Vol. 24, No. 2, African Americans in Art: Selections from the Art Institute of Chicago (1999), p. 162-179, 262-265.

Powell, Richard J. “Re/Birth of a Nation” in Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance. Exhibition Catalogue. London: Hayward Gallery, the Institute of International Visual Arts, 1997.

Awesome blog, Mary!! And I, of course, would love to see a post dedicated solely to Jean-Michel Basquiat 🙂

Mary. This is simply fantastic. I couldn’t be more proud. And Emi will just have to read my JMB book (coming next year) 🙂

All best,

Jordana

On a slightly different tangent, Egmond Codfried has made a study of the erasure of “blackness” from the portraits of nobility in Europe, demonstrating revisionistic history, and supporting Adrian Piper’s view that many whites have a statistically black ancestry. Codfried wrote the somewhat controversial book, “Blue Blood is Black Blood”, and I shared a reprise of his work here: http://starinthestone.wordpress.com/2012/11/14/black-blood-blue-blood-an-alternate-view-of-european-history/ . His response to me is interesting.

I really enjoyed your post on the topic; especially the discussion towards the end about the construct of and existence (or not) of race. Thank you for responding and sharing your own work!